Business travel: ‘We don’t know how many people will choose to fly’

A senior executive at US transport and defence infrastructure company Cubic, Ian Woodroofe, has notched up a business trip “probably every week” — often overseas — for more than 20 years.

Trips were always business class and he had two or three loyalty cards for airlines and hotels. But as coronavirus rapidly spread last year, Mr Woodroofe was grounded, his San Diego office promptly closed and all travel cancelled. “I haven’t travelled since March,” he says.

Nor have millions of other business travellers, leading to a $710bn year-on-year loss of revenue to the industry. The question now is whether those travellers will return once the pandemic ends. And, if they don’t, what that means for a sector which directly and indirectly supports one in seven jobs worldwide according to the Global Business Travel Association, subsidises mass tourism and had annual revenues of $1.4tn in 2019.

$710bn

The expected loss of revenue for the business travel sector since the start of the pandemic

Cubic managed to hit its annual targets last year thanks to a healthy use of the video conferencing platform Zoom, which announced in December a 485 per cent year-on-year increase in clients with more than 10 employees. “You can do a lot of business without actually meeting clients face to face,” says Mr Woodroofe, adding that once the pandemic ends he does not plan to travel anywhere near as much.

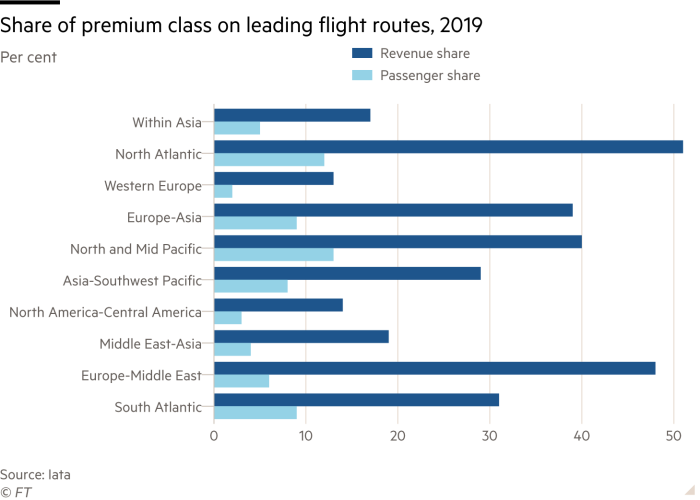

So although many in the travel industry are predicting a robust recovery in leisure travel once borders can properly reopen as cooped-up workers make a break for overseas trips, business travel, which can generate as much as 75 per cent of airlines’ revenue on some international flights, according to PwC, faces a severe crisis.

Together with a greater focus on sustainability and post-pandemic cost cutting at financially straightened companies, the uptick in virtual gatherings is likely to have long-term consequences, industry executives say. Some have likened the disruption in corporate travel to the accelerated decline of bricks-and-mortar retailers at the hands of their online rivals.

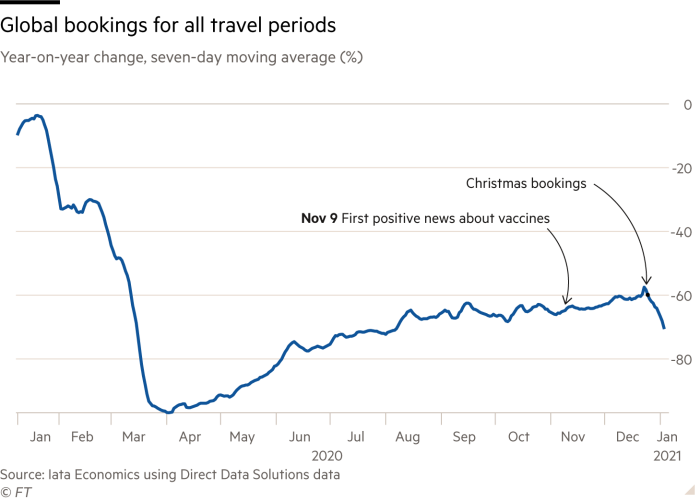

Many in the sector accept that a chunk of business travel will be lost. But with vaccination programmes being rolled out globally, there is little agreement on how much that loss will be or how long the fallout will last.

Bill Gates told CNBC in November that “over 50 per cent of business travel and over 30 per cent of days in the office would go away” — a prediction dismissed by Ed Bastian, chief executive of Delta Air Lines, who countered that the Microsoft founder was not qualified to forecast the future of corporate travel.

Yet even within the travel industry, there is uncertainty about how much business travel will return.

Jeffrey Goh, chief executive of Star Alliance, the world’s largest airline group, predicts there will be a “structural change in terms of the business travel segment” that could leave the sector up to 30 per cent smaller. Yet Carsten Spohr, chief executive of Germany’s Lufthansa — a Star Alliance member — insists that business travel is set to return quickly. “Whenever I talk to corporate customers, there’s such a backlog of travel needs,” he told a recent analyst call.

“There is a grey area and lots of unknowns in relation to business travel,” says Martin Ferguson, vice-president of public affairs at American Express Global Business Travel, one of the world’s largest corporate travel management companies. “At the moment you can’t travel so even if you wanted to, you can’t.

“[What] we don’t know,” he adds, “is how many people will choose not to [travel] when they can.”

Pre-emptive action

The explosion in air travel during the 1950s and 1960s triggered exponential growth in the number of executives criss-crossing the globe. They have long propped up the industry by expensing higher priced, refundable airfares and more expensive hotel rooms with space for work and, more recently, Wi-Fi facilities.

A seat in business or first class is on average five times more expensive than in economy, according to the global airline trade group Iata, and airlines rely on these premium seats for 30 per cent of their revenues. Marriott, the world’s largest hotel group, estimates that in 2019 around 70 per cent of its hotel nights were business-related bookings.

75%

The percentage of airlines’ revenue generated by business travel on some international flights, according to PwC

The pandemic has already accelerated the demise of fuel-inefficient Boeing 747 planes, which are set up for a large number of premium seats and have been retired early at big carriers including British Airways, where they were due to fly on until the middle of this decade. Some airlines have also grounded the larger A380, which could be fitted out with suites, showers and bars for first and business-class passengers — an acceleration of a pre-pandemic trend towards smaller, nimbler aircraft.

Such is the reliance of major travel companies on their corporate clients, says Dave Hilfman, interim executive director of the GBTA, that the drop in revenues will push up prices for leisure customers: “A lot of [the travel industry’s] business model revolves around corporate and business travel, and because of their ability to generate higher margins and profit [in that sector] it allows them to extend opportunities to the more discretionary and leisure traveller.”

Yet the growth in business travel had been slowing globally, according to the GBTA. In the UK, the fourth-biggest economy in terms of business travel expenditure, for example, data from the Office for National Statistics shows that while international air travel for leisure increased 3.4 per cent per year between 2000 and 2019, international business travel grew just 0.2 per cent annually.

Corporate travel also saw more sluggish growth than holiday bookings after both the September 11 terror attacks and the 2008 financial crash and the GBTA estimates that business travel spending losses will be 10 times larger than during either of those two crises. According to a report by consultants McKinsey, international business travel from the US took five years to fully rebound after the 2008 recession, compared with a recovery of leisure travel within two years.

Yet, to refer to business travel as a “monolith is dangerous”, says Mark Hoplamazian, chief executive of Hyatt Hotels. “Different segments will have different impacts.”

$81bn

The value of the exhibition and trade show industry, which is expected to be among the last business travel sectors to recover

In China, where domestic and regional travel has resumed to varying extents, industrial and manufacturing companies have been at the forefront of the corporate travel recovery, while service industries that are easier to operate remotely have been slower.

The McKinsey report predicts that intra-company travel for training or inspections is likely to be “decimated” as corporations look to minimise costs, and that major business conventions, including the exhibition and trade show industry which was valued at $81bn in 2018, will be the last to return. For the first time in its history, the Consumer Electronics Show, the world’s largest trade convention that normally takes place in Las Vegas, was held entirely online this week.

Need for co-ordination

“Global travel thrives on certainty, simplicity and harmonisation,” says Robert Sinclair, chief executive of London City Airport. But efforts to kickstart a recovery in the travel sector have been hampered by a lack of international co-ordination on the rules governing cross-border movement of people throughout the crisis.

The UK and Canada only introduced mass testing for incoming passengers in January, months after many other countries introduced similar measures. Attempts to start so-called “travel corridors” have stuttered, with plans stalled for Covid-secure passage on the highly profitable London to New York route and an attempt to start a travel bubble between Singapore and Hong Kong called off a day before the first planes were due to depart in November, after a rise in cases in the Chinese territory.

Several competing digital health passes have been launched, promising to certify passengers who have tested negative for Covid-19 or been vaccinated before they get to the airport, but none has yet been rolled out on a significant scale.

Beata Sperling-Tyler, a senior credit analyst at S&P Global, says companies want certainty before they send employees out on the road: “It’s worth referring to what happened after 9/11 — airports had to become terrorist-proof and now they have to become virus-proof.”

Avi Meir, chief executive of Travelperk, which provides travel booking technology for businesses such as Airbus, says that while the company’s corporate bookings are 70 to 80 per cent lower than 2019 levels, it has gained clients by developing a service that provides travellers with real-time updates on restrictions and health requirements.

“It is driving half of the deals we win right now,” he says. “The constraints [on bookings] are external: the virus and health concerns and regulation and restrictions. There isn’t a shift in how people view travel.”

According to the GBTA’s latest poll of its members, only 6 per cent envisage any international business travel in the first three months of 2021.

Some business travel providers are hedging against a sustained drop in corporate volumes. Airlines are looking to open up more routes to leisure destinations to offset the ones lost by the decline in business traffic, as they scramble to redesign their networks.

Accor, the hotel group behind the Sofitel and Ibis brands, previously relied on business travel for around two-thirds of its revenues. But it has bought out the remaining stakes in its boutique hotel brands — at a cost of around $500m — and is merging them into a new $1bn company with the Hoxton hotels owner Ennismore, in which it is the majority shareholder. With its own dedicated management team, the hope is that the portfolio will grow much quicker.

The company is also in the early stages of making unused floors of its hotels available to companies to set up remote working hubs.

“Accor has decided to go very, very deep on buffering what could be a loss in business travel,” says Sébastien Bazin, chief executive of the Paris-headquartered company, who predicts a permanent reduction of between 7 and 10 per cent in business custom. Based on 2019 revenues that could amount to more than €200m, and while it has €4bn of liquidity, it has cut its dividend, slashed costs and furloughed many of its 310,000 employees.

Hilton and Marriott have similarly started marketing empty hotel rooms as space for workers who don’t have the luxury of a home office, and have invested in medical-grade cleaning procedures and contactless check-in for those that do need to make overnight trips.

Satya Anand, president of Marriott’s Europe, Middle East and Africa division, says the group has also started to offer “new health protocol options” for meetings in its US hotels. Businesses making group bookings at its Gaylord hotels in Florida, Tennessee, Texas, and Colorado can opt for different testing regimes and pre-screening questionnaires to be included in their package.

Cutting costs

The empty skies that contributed to a fall in pollution levels in some countries in 2020 are also driving sustainability up the corporate agenda. A feasible way to dress-up cost cuts is to rebrand reductions in travel as environmental initiatives that will bring companies closer to net-zero emissions targets, says Ms Sperling-Tyler.

Despite rising optimism around vaccinations, a Deloitte survey of 90 finance directors across the UK’s largest companies in January showed that 44 per cent expected to reduce discretionary spending such as travel even further over the next 12 months. The CFOs are also anticipating a fivefold increase in homeworking relative to pre-pandemic levels by 2025.

Among the companies that have already pledged to reduce travel include consultancies such as Deloitte and PwC, consumer goods group Nestlé and Allied Irish Banks, which said a commitment to permanently reduce business travel had been “naturally” accelerated by the pandemic.

Yet Ariane Gorin, president of the travel platform Expedia’s business services division, points out that a more sustainable travel programme does not necessarily mean a smaller one. “What has been interesting about Covid-19 is that it has allowed many companies to reset their travel programmes from a baseline of zero, giving them a great opportunity to rebuild it with their particular corporate social responsibility agenda in mind.”

One of the beneficiaries of this rebuild could be rail. When the French government agreed to a state aid package for Air France it stipulated a 50 per cent reduction in CO2 emissions on medium and long-haul routes by 2030 and required the airline to cut emissions by half on short haul routes where trains could offer a journey time of two-and-a-half hours or less. The air bridge between Barcelona and Madrid, operated by Iberia, is also under threat of being cancelled by officials in favour of trains.

Whatever the means of travel, Marriott’s Mr Anand, who has worked in the industry for more than 25 years, says the need to recuperate the trust that fuels business relationships will drive the industry back: “While virtual working is great for doing the day job, nothing beats face to face when you want to seal the deal.”